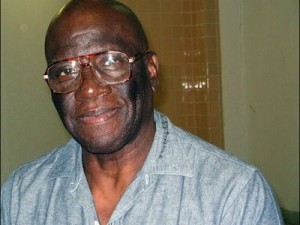

[I spent a couple of days in early October helping care for Herman Wallace, who died on October 4th. I wanted to write something about his death, and here it is. – DMZ]

On October 4th, 2013, at 7:30 a.m., Herman “Hooks” Wallace died in New Orleans’ Twelfth Ward, surrounded by family and supporters. He had been free from prison for only three days after spending 41 years in solitary confinement in Angola Prison, part of a group of political prisoners, along with Albert Woodfox and Robert “King” Wilkerson, known as The Angola Three.

The three men met in Angola Prison in 1971, where they were serving time for armed robbery. In response to the brutal treatment that prisoners were receiving at the hands of the guards they formed an Angola Prison chapter of The Black Panther Party. In 1972 Woodfox and Wallace were accused of murdering a prison guard and received life sentences, to be served in solitary confinement. The two men always maintained their innocence and claimed that they had been unjustly railroaded by the Louisiana courts as punishment for their political organizing. They became known as The Angola Two and were supported in their plea for justice by the then very active New Orleans Black Panthers.

But the New Orleans Panthers were organizing in what was at the time arguably one of the most repressive political climates in the U.S. Constantly threatened with eviction from the offices they rented, and involved in two armed shootouts with police, the N.O.L.A. Panthers eventually took up residence in the Desire housing projects, where residents helped defend them from police attacks.

During this same period there was an active Angola Two Support Committee in New Orleans. However, supporters were eventually to learn that two of the main organizers of the Committee were F.B.I. informants, part of the government’s “Cointelpro” program which targeted and informed on thousands of activists from the 1950’s through the early 1970’s.

As a result of these and other pressures, both the New Orleans Black Panthers and the Angola Two support committee dissolved around 1975. And for the next twenty-one years, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox were on their own, members of political movements that were now being relegated to history books and documentary films. Locked in solitary confinement in a prison that had once been a slave plantation, the Angola Two joined the ranks of the U.S.’s long list of political prisoners from that period including other Black militants like Geronimo Pratt and Mumia Abu Jamal, American Indian Movement activists like Leonard Peltier, and Weathermen like David Gilbert and Marilyn Buck.

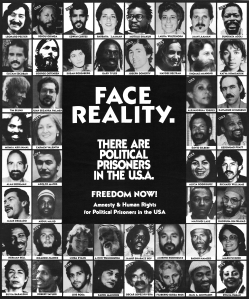

In 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected president and a concerted campaign began to admonish the social movements and radicals of the 1960’s as deluded dreamers who had done the world more damage than good. Nonetheless, these imprisoned militants of yesteryear inspired my own generation of political activists as a cause worth supporting, for they had all received sentences far beyond what crimes identical to theirs usually received, and were clear cases of U.S. government repression against political agitators. I was introduced to many of them through a book called “Hauling Up The Morning” which was an anthology of writings by political prisoners, and one of the first political posters I ever put on my wall was one that featured rows of pictures of the nation’s political prisoners with the words “Face Reality: There Are Political Prisoners In The United States” emblazoned across its top. A bit strident perhaps, but I was twenty-one years old.

Even so, I still didn’t hear about The Angola Two case until 1998, during the lead-up to the first-ever nationwide gathering of anti-prison campaigners, called Critical Resistance, which was to be held in Oakland, California in the summer of that year. The organizers of the conference received a letter from Herman Wallace, explaining the case of The Angola Two and asking for the support of Critical Resistance, especially as Albert Woodfox was about to be granted a new hearing in his case.

I was living in Austin, Texas at the time and I got a call from Scott Fleming, a lawyer in Oakland who was helping with Critical Resistance. He read Herman’s letter to me and asked if I knew anyone in Louisiana who might be able to set up a new support committee for The Angola Two. I told Scott that I had heard there was a radical bookstore that had just opened in New Orleans called The Crescent Wrench and maybe that would be a good place to start.

Brackin Camp, one of the collective members at Crescent Wrench, remembers a local organizer named Malik Rahim coming into the bookstore, introducing himself, and telling them about The Angola Two. Albert Woodfox’s hearing was set to happen in a few weeks’ time and Rahim was looking to organize transportation to attend the proceedings. The Crescent Wrench volunteers threw in, Malik, Brackin and others drove to attend the hearing, and that year the Angola Two Support Committee was re-born.

Around that time a very important chapter in U.S. history was beginning, albeit one that went unnoticed by large numbers of people and the media: the incarcerated population of the United States exploded, hitting 2.1 million people (depending upon how one counted), up from 300,000 in 1978, making the United States the country with the highest number of people under the control of it criminal justice system in the world. And in 1996, for the first time ever, the number of people incarcerated in United States prisons for non-violent crimes surpassed the number of people convicted of violent crimes.

Much of the responsibility lay with the country’s “War On Drugs”, begun under Reagan and continued under Bush pére and Clinton, which mandated draconian “mandatory minimum” sentencing guidelines for scores of offences and led to the construction of “supermax” prisons around the country. Prisons and prisoners became the focus of organizing and activism around the U.S., and in Austin we organized a project called The Inside Books Project, which sent free books to Texas prisoners, who for the most part lacked libraries or any other amenities which might make their time in prison in any way helpful to them or society. All talk about rehabilitation or reform were long gone from U.S. prisons, and Texas was no exception. Through Inside Books Project we tried to publicize the issue of prisons and prisoners, and The Angola Two became our local political prisoner cause célèbre.

Herman Wallace was a tireless advocate of the Angola Two, constantly writing letters about the case to whomever would listen, and he and I began to talk on the phone regularly, him calling me from inside Angola Prison and me answering him from my apartment in Austin. We also exchanged many letters, and at that time I was hosting a program on Austin’s KOOP radio about prisons and I would read his letters over the airwaves whenever I received them.

I remember Herman calling me when Bill Clinton was leaving office, expressing his frustration that Marilyn Buck, another U.S. political prisoner, had not been released. I couldn’t believe I was listening to a man who had been buried alive for so many years lamenting about another prisoner’s misfortune. Make no mistake – Herman Wallace was one of the most selfless people I would ever come in contact with.

It was around that time that Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox asked their supporters on the outside to include another inmate as part of their case: Robert “King” Wilkerson, who was also a member of the Angola Black Panthers and was also interned in solitary on equally dubious charges. As their supporters we obliged and The Angola Two were re-christened The Angola Three. We kept spreading the word wherever and whenever we could, but the three men remained in solitary in Angola.

One cold February day in Austin in 2001, Scott Fleming again called me from Oakland and told me I needed to get ahold of a camera and get myself to Louisiana as quickly as possible because it looked as if Wilkerson’s conviction was about to be overturned. I borrowed a Sony XL-1 video camera from Isaac Mathes, a film school buddy, and drove to Saint Francisville, the home of Angola Prison.

That day is forever burned into my synapses, as a small group of supporters waited outside the prison gates for several hours on a warm Louisiana winter day, and then we watched as the doors of Angola Prison slid open and Robert “King” Wilkerson walked out to meet us after spending 29 years in solitary confinement.

There followed a massive “Second Line” street party in New Orleans, led by The Soul Rebels Brass Band, and we all danced in the streets and sang “King is free!” until our voices were hoarse. I drove back to Austin and cut a short film from the footage called “King Is Free”, and it remains the most widely-viewed piece that I have ever produced. King himself did not waste a minute upon his release but immediately threw himself into speaking and organizing about The Angola Three, and he and I remain close friends to this day.

That same year, 2001, it felt to many of us that the situation of prisoners in the U.S. was finally reaching a critical mass of popular awareness. In March of that year governor Pat Quinn of Illinois abolished that state’s death penalty after courts threw out the death sentences of 13 condemned men. Nationwide it seemed that the idea of having more people behind bars for non-violent offences than for violent ones was beginning to prompt a much-needed re-thinking of the country’s draconian sentencing guidelines, particularly those having to do with the ongoing “War On Drugs”, which was widely seen as little more than an abject failure on its own terms: there were now more prisoners than ever in U.S. prisons and yet drugs were more available than ever before. What, it was finally being asked, was the point?

And then came the events of September 11th, 2001, and the subsequent march to war in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. The “War On Drugs” took a back seat to the “War On Terror”, and the issues of the nation’s prisons and prisoners were forgotten, for the moment it seemed, as the government launched into another round of attacks against civil liberties in the name of preserving “freedom.”

And Wallace and Woodfox remained in solitary confinement in Angola Prison. We all continued trying to keep the case in the public eye. And in that sense The Angola Three support committee was very, very lucky because more people kept joining in to help the cause.

In 2002, Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop chain of stores, took an interest in the case, and began running ads about the Angola Three, and eventually would pay for legal fees on Woodfox and Wallace’s continued appeals.

Of the men in the Angola Three, I always felt that Herman was The Joker. Brash and talkative, his recourse throughout his decades of imprisonment was always his never-failing sense of humor. And so it didn’t surprise me to hear in 2003 that he had began a collaboration with an artist named Jackie Sumell called “Herman’s House” in which he described his spacious, comfortable ideal home, in stark contrast to the 6-foot by 9-foot cell that he had lived in for three decades. Sumell made computer-drawings and scale models of Herman’s dream house, and presented it as an art installation in galleries around the world, always using it as a way to talk about the Angola Three and prisoners in the United States. Herman said that the project, “helps me to maintain what little sanity I have left, to maintain my humanity and dignity.”

In 2010, director Vadim Jean produced a feature documentary about the Angola Three called “In The Land Of The Free”, which was narrated by Samuel Jackson.

It seemed like prisons and prisoners in the U.S. were, once again, entering the public discourse. The government’s continued steamrolling of civil rights under The Patriot Act, coupled with the economic depression, was causing people to question the number of incarcerated people in the country. Perhaps the most visible example of this was that in July 2011 prisoners who were being held in solitary confinement in California’s notorious Pelican Bay Prison called a truce between prison gangs and organized a state-wide hunger strike to draw attention to their plight. At its peak it involved 6,600 men in 13 jails, and they followed it with a second two months later, and then another in July 2013 that involved over 30,000 inmates.

In 2013, Angad Bhalla directed a film for PBS about Wallace and Sumels’ artistic collaboration called “Herman’s House”, which was broadcast nationally in July.

In June of 2013, Herman Wallace was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. His medical attention in Louisiana’s prison system was hardly adequate, and by the time his illness was discovered it was unclear just how much longer he would have to live. His lawyers and supporters appealed for a compassionate release on medical grounds and as expected the state refused. After months of waiting, and with Wallace’s condition deteriorating daily, on October 1st, 2013 a federal judge overturned Wallace’s original conviction, making him a free man, and his supporters arranged a room in a private house with medical facilities in New Orleans to receive him.

But at the eleventh hour the state of Louisiana once again showed its true, brutal, racist colors as the East Baton Rouge District Attorney sought a court order blocking Wallace’s release. With an ambulance waiting outside the prison hospital to take him to New Orleans, a standoff ensued over the custody of a weak, terminally ill, 71-year-old man who had spent the last 41 years in solitary confinement. When Ed Pilkington of the U.K. Guardian described it as a “gruesome legal battle” he was making an understatement. There was an almost awe-inspiring clarity to the sheer inhumanity, and total absence of compassion, being displayed by the prosecutors in Baton Rouge. It was as if they were reminding us: lest you forget who you are dealing with. Maybe Americans should be reminded of this more often.

But after several hours of legal wrangling the D.A. backed down and Herman was finally released from prison and driven to New Orleans. And as luck, or coincidence, or New Orleans magic would have it the house that his supporters had prepared for him happened to be on General Taylor Street in the Twelfth Ward – just one block from the very house that Herman Wallace and his eight siblings had grown up in back in the 1950’s. As I boarded a plane in San Francisco to fly New Orleans I couldn’t help but think that wheels were turning and circles coming closed, and in some way Herman the Joker was making sure that everything was lining up just the way he wanted it to.

And now he was free, although he was confined to bed. The state of Louisiana made one last ugly move and re-indicted Wallace just two days after he was released and we all panicked for a few hours, thinking that police cruisers would be descending upon the house at any moment to drag Herman back to prison. It turned out to have likely been little more than the D.A. trying to save political face, but it was a last insulting “parting shot” from the authorities.

In any event, Herman Wallace only lived for another twelve hours or so after that. The sun was rising over New Orleans when he died at around seven thirty a.m. the next day, peacefully and in his sleep. I like to think that in his own way he was “hauling up the morning” as he left us, and the last words he spoke were, “I love you all.”

I’m at a loss as to what to say about a man whose life was stolen from him, except to remember that one should always pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living. I do want to say this though: it is important to remember that the situation of prisoners in the United States is not merely a cluster of cases similar to The Angola Three. In other words what we have is not a group of “bad apples” or “flaws” in the U.S. penal system; it has as much to do with social control and endemic racism as it does with the whims of even the most deranged Louisiana district attorneys. It’s a subject that must be unpacked in a book (or several books) rather than in a single article, and I encourage the interested reader to pursue the resources I have referenced below. There are on a given day around 80,000 people in solitary confinement in United States prisons but they are just one part, albeit a particularly awful one, of a much larger and more insidious system that has, in the words of the incarcerated organizers of the California prison hunger strike, created a “prisoner class” in the U.S. This is not a problem that is simply going to vanish, and is one that will have profound effects upon society for decades to come.

They say that a prisoner’s biggest fear is of being forgotten. Maybe our responsibility as a society is to remember that we can’t simply continue on with a country that has so many incarcerated people, and begin to address real prison reform, and as a nation decide that burying people alive is no sort of solution to societal woes.

David Martinez is a writer and filmmaker based in San Francisco. His most recent film is Autumn Sun: A Story About Occupy Oakland and it may be viewed here:

https://dmz2008.wordpress.com/autumn-sun-2/

He may be reached at: moleverde@gmail.com

For more on prisons and prisoners in the United States, here are some good resources:

The Herman’s House Project: http://hermanshouse.org/

The Herman’s House Film: http://hermanshousethefilm.com/

Books:

Lockdown America by Christian Parenti

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California by Ruth Gilmore

Green is the New Red: An Insider’s Account of a Social Movement Under Siege by Will Potter

From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of a Black Panther by Robert “King” Wilkerson

Showdown In Desire: The Black Panthers Take A Stand In New Orleans by Orissa Arend (about the New Orleans Black Panthers)

Projects/Websites:

Solitary Watch

The Sentencing Project

http://www.sentencingproject.org

Critical Resistance

http://criticalresistance.org/

Films:

In The Land Of The Free directed by Vadim Jean

http://www.inthelandofthefreefilm.com/

Safety Orange directed by James Davis and Juliana Fredman: